Travelling too fast (possibly even recklessly!), come to a corner and slide into a brick wall, only to be left picking up the pieces – metaphorically speaking. Describing the ‘impact’ that an organisations activities have through a staff perspective proved to be a bit like hitting a brick wall at speed. Not the desired impact.

The staple food in Malawi is ground maize meal, cooked into a thick paste called nsima. It’s sometimes referred to as ‘food’ by the locals, because anything else is considered merely ‘relish’, or an accompaniment. Unfortunately whilst nsima is incredibly filling, it is almost completely nutrition free. The consequences of this cultural phenomena are dire. The UNDP writes “Malnutrition remains a challenge and the single biggest contributor to underweight children under the five years of age and child mortality. If the current trend continues, about 32 percent of children will be underweight by 2015 which is 18 per cent more than the (Millenium Development Goal) target.” These children are malnourished because they’re fed an exclusive diet of nsima. Food production and eating are cultural activities, and people only change accepted cultural practice or tradition at their own pace.

Grace scooping nsima out of the pot. Each glutenous pod being a serving.

How we describe the ‘truth’ is equally subject to cultural tradition. Wikipedia states that ‘There are differing claims on such questions as what constitutes truth: what things are truthbearers capable of being true or false; how to define and identify truth; the roles that faith-based and empirically based knowledge play; and whether truth is subjective or objective, relative or absolute.’ In other words whether one prefers the truth as described by a science undergrad or that of Hunter S Thompson is in itself one of cultural tradition. In a complex world with multiple truths, both are more or less right. Difficulties generally arise when the belief is that there is only one truth, in much the same way as believing there is only one food. Despite being a truism, what one believes to be true, is true. Unfortunately a critical factor in todays world is who has the power to define the truth, – even when describing how to identify and describe truth itself.

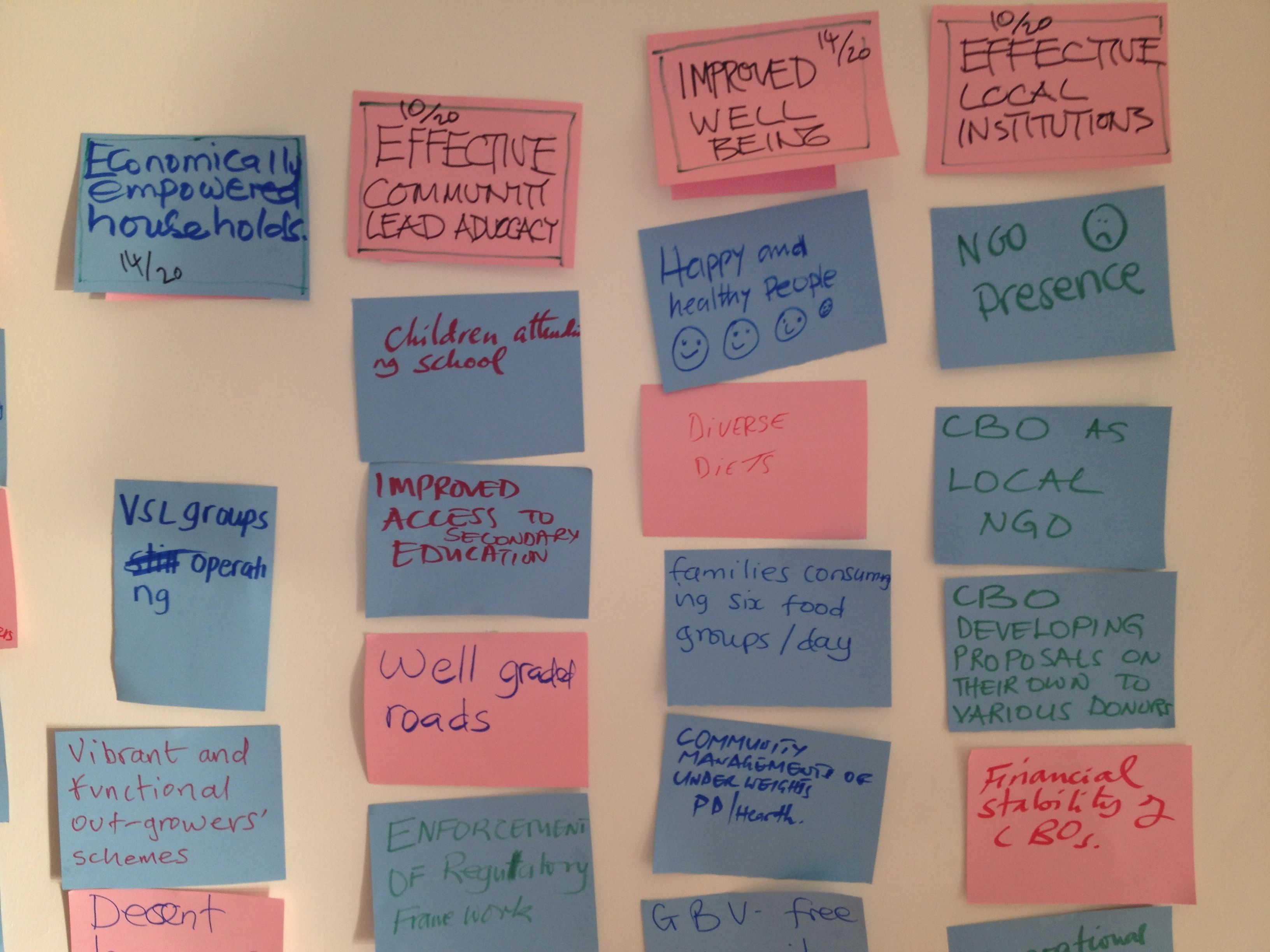

Multiple stories leading to an agreed truth. In a workshop I asked Livelyhood project staff ‘What legacy of your project would you hope to find 2yrs after you’ve left an area?’. After grouping their answers, I then asked ‘what chance do you expect your project would achieve each aspect?’. Of those in this photo, answers were: Economically Empowered Households 70% chance; Effective Community Lead Advocacy 50%; Improved Well Being 70%; Effective local institutions 50%.

So, whether an impact report based on staff perceptions of ‘impact’ is more or less true than something with figures and an impression of objectivity is in itself subjective. I say ‘impression’ of objectivity because whilst ‘objectivity’ is the dominant culture of describing ‘truth’, it is still only a cultural tradition, and possibly only relatively appropriate when describing change in a highly complex environment with infinite factors and parameters. So, a bit like telling a Malawian that nsima isn’t that good for them, I’m left surveying the wreckage caused by attempting to describe an organisations ‘impact’ in a different manner to the accepted tradition. Which leaves me wondering how and where to start putting things back together.